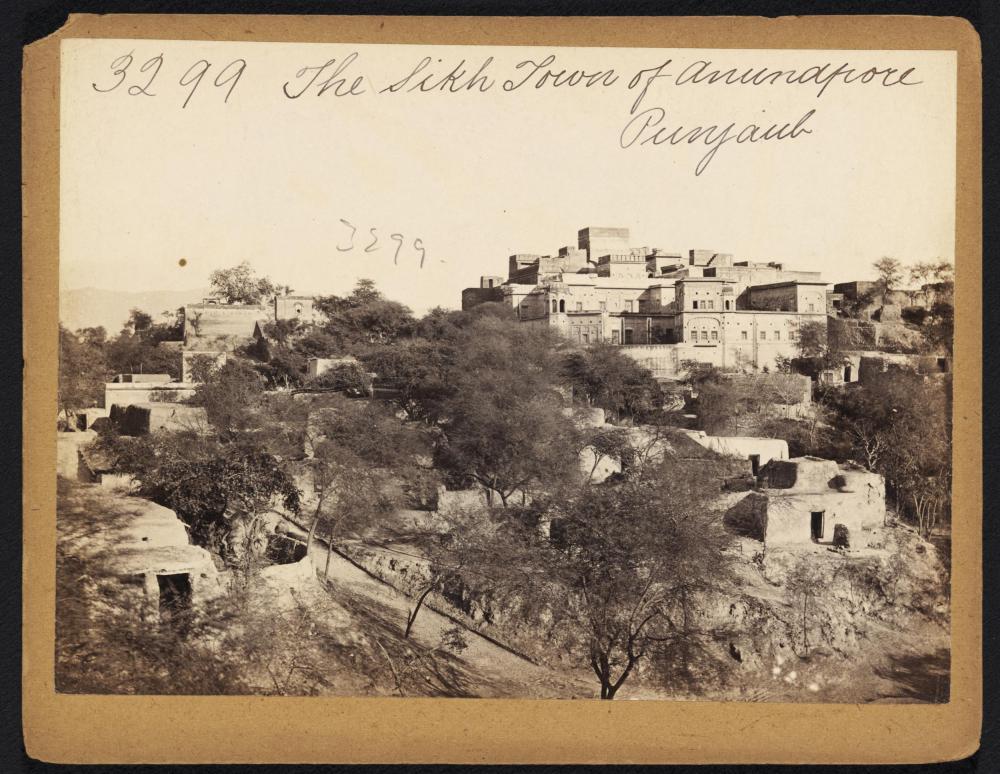

It’s an especially bitterly cold, rainy and wet December in 1704, when Guru Gobind finalizes his decision to evacuate Anandpur. This resolve is not an easy one given waves of unrelentless enemy attacks, weakened state of his men (enfeebled from starvation due to the prolonged 8-month siege), and the unwavering resolve of Gur Sahib himself to rid the subcontinent of abject tyranny and subjugation of its rulers. Evidently, Gur Sahib’s meteoric rise, his expanding popularity and growing political influence in the area, was very unpalatable and threatening to the ‘Pahari Rajas’ (Hill Chiefs of the neighboring principalities), and to Wazir Khan, the governor of Sirhind (a quintessential Mughal territorial center). Therefore, to subjugate him, they repeatedly harass and ambush him (and his Sikh resistance), as witnessed by the battles of Bhangani (1688), Nadaun (1691), Guler (1696), Anandpur (1700 & 1701), Nirmohgarh (1702), Basoli (1702), 1st war of Chamkaur 1702), etc.

The final and full-on assault on Anandgarh Fort happened on May 20th, 1704. It was a formidable one! A coalition enemy army, a million soldier strong, was assembled (contrived from a military alliance between Mughal forces from Sirhind, Lahore and Kashmir territories; troops of Pahari kingdoms from Kahlur, Kangra, Kullu, Kionthal, Mandi, Jammu, Nurpur, Chamba, Guler, Garhwal, Bijharwal, Darauli and Dadhwal; and tribesmen from Gujar and Ranghar tribes of Bajrur). This gigantic army clearly had an unfair and disproportionate advantage; they began their assailment to annihilate the Khalsa bastion (about 4000 strong). Despite the enormity of the attack, the Khalsa were able to successfully engage and thwart all attempt of this herculean army. This tenacity, persistence and resoluteness of these unflinching defendants, led the syndicate to change their campaign to that of besiegement. Hoping to draw them out thru starvation, suffering and desperation, the burgh was barricaded, and all access to food & essential supplies were cut off. Simultaneously, they continued to provoke, hackle and exasperate them including unleashing an intoxicated elephant so that the Lohgarh gate, an iron gate of the fort, could be broken (that Bachitter Singh thwarted). Plus, capitalizing on Guru’s sense of honor, the Rajas falsely pledged their vow (that would allow Guru and his group to leave safely) on revered Hindu articles of faith (i.e., pious cow and ‘janeau’, the venerated thread). Gur Sahib fully aware that Pahari Rajas could not be trusted, demonstrated their insincerity (and fallacy of their oath) by masterminding a sham evacuation that was promptly attacked and plundered. Thereby exposing their true intentions and greed!

There were also calls for desertion and defection. The enemy publicized that whosoever rejected Sikh beliefs and proclaimed that they were not Guru Gobind Singh’s Sikhs, would be allowed to leave safely, unharmed! Some men from Majha, led by Mahan Singh, apprised Gur Sahib of this intention. Guru in return asked them to write and sign this ‘be-da’wah‘ (disclaimer of not being a Sikh). Upon receiving this deed, the Gur declared “From now on, you are not my Sikhs and I am not your Guru” and allowed them to leave. However, when they returned home, their women did not accept them and shamed them for their desertion and cowardice. Subsequently, they redeemed themselves in the ‘1706 Battle of Kidrana Lake’ (now Mukstar), where under the command of Mai Bhago, the great female general, they laid down their lives fighting valiantly for the Guru. Mahan Singh, breathing his last, begged Guru Gobind Singh for forgiveness, handed him the aforementioned ‘beda’wah‘, and pleaded to him to tear off that shameful statement (whereby allowing them to return to the fold of the Guru). Their martyrdom has a special place in Sikh annals as ‘Chalis Mukte’ (Forty Liberated Ones), and each time the Ardas (prayer of remembrance) is said, their sacrifice is recalled!

Alamgir Aurangzeb

Auranzeb’s Handwritten Quran

The eight months of beleaguerment concluded with the arrival of the ‘Shahi Parwan’ (a royal decree) from the emperor himself. Inscribed and signed on the pages of the holy Quran, was the Aurangzeb’s covenant assuring protection and desire for a future meeting in Dina. Gur Sahib, compelled by the suffering and desire of his people, and against his better judgment and prudence, accepts this armistice. Arrangements were made to evacuate the fort, heavy guns disbanded, certain weapons/equipment destroyed, and other relics and manuscripts burnt. However, this consecrated pledge of the emperor, as envisaged by Gur Sahib, was also a ruse, a ploy and a cunning gameplay to draw them out.

This resolve to leaving Anandpur on December 20th is about to test the mettle, ideals and faith of Gur Sahib. As soon as they left their bastion, they were pursued relentlessly by this huge opposing enemy. At ‘Shahi Tibbi’ near Nirmoh (also called the Battle of Sarsa), a contingent of the Sikh armies engaged the armies of Wazir Khan and for three hours kept them at bay. Both sides suffered heavy casualties but it allowed the Guru and his retinue to reach the swollen Sirsa River. Due to flooding, fast currents, and frigid temperatures (compounded by starvation and fatigue), few could only navigate the treacherous river. Even the Guru’s family got separated! Gur with his two elder sons (Ajit Singh and Jhujjar Singh) and 40 of his stalwarts, successfully maneuvered their horses and crossed the river. Whereas, his two youngest sons (Zorawar Singh and Fateh Singh) and their grandmother (Mata Gujari), unable to traverse the creek, ended up in ‘Saheri’, the village of Gangu Brahmin, their trusted household cook. So, with the imperial armies hot on their pursuit, the Guru’s entourage took refuge in a ‘Garhi’ (mud fortress) in Chamkaur (that was reknownrd for its strategic location). This set stage for the epic battle (also called Chamkaur Di Garhi or Garhi Chamkaur Di), and it fulfilled Guru Gobind Singh’s famous proclamation-

Chiriyan To Mein Baaz Laraun (I’ll Train the Sparrow to Fight the Hawk)

Gidran To Mein Sher Banaun (I’ll Teach Jackals to Become Lions)

Sava Lakh Se Ek Laraun (I’ll Prepare One to Fight Quarter Million)

Tabhi Gobind Singh Naam Kahaun (Then Only Can I Be Called Gobind Singh)

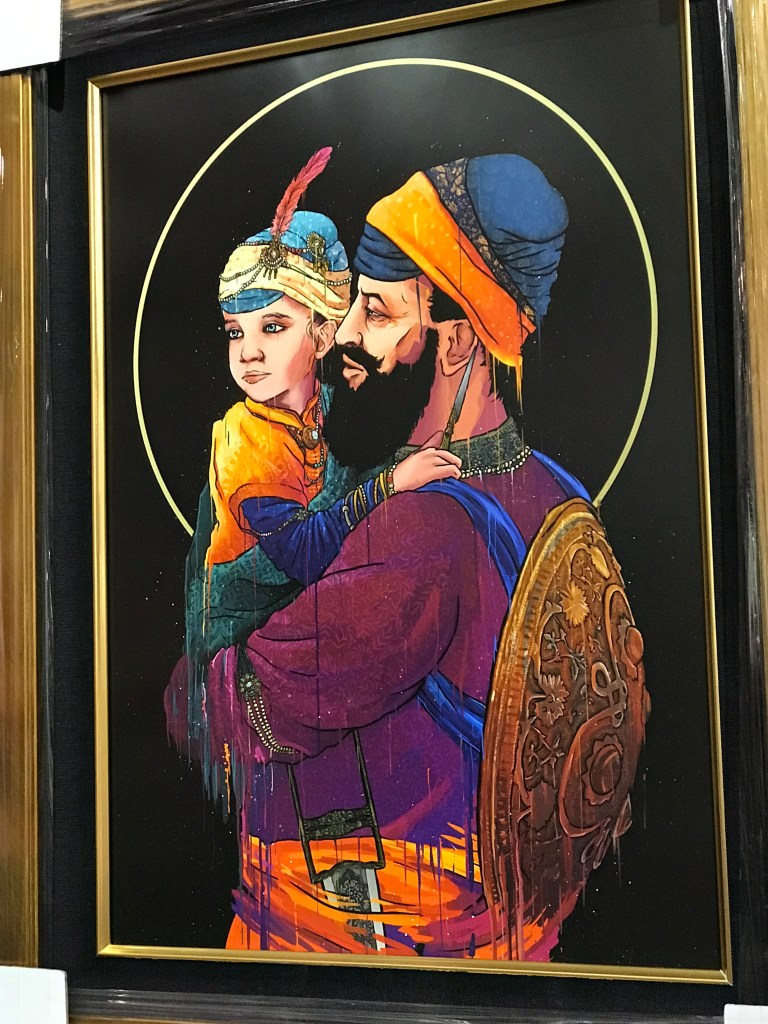

Guru Gobind Singh

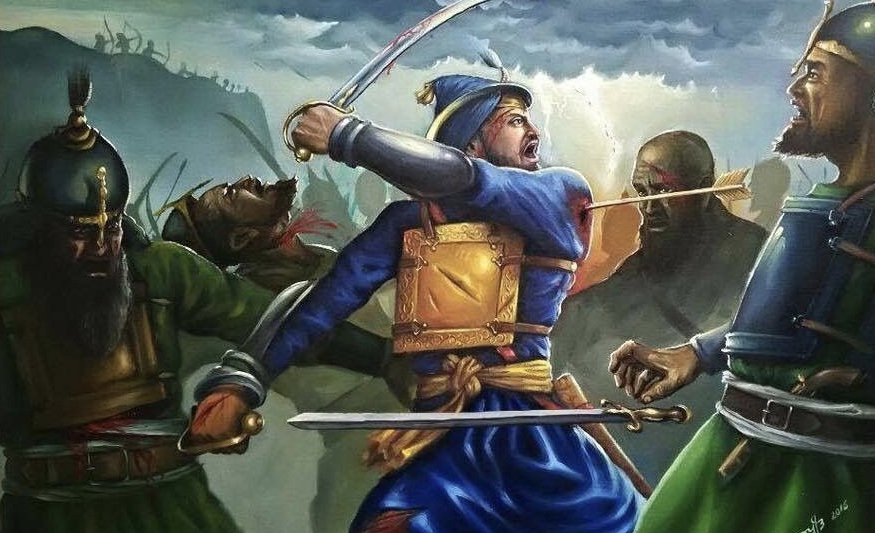

Against overwhelming odds, 43 surrounded by a million (yes, a million), every defendant knew death was inevitable! Also evident was that the ‘Garhi’ and its defenses would succumb under pressure of this imposing onslaught. The Guru, already a warrior extraordinaire, a military genius and a meticulous war planner, readied his team for an intense combat. He orchestrated and executed a well thought thru offensive that considered the weaknesses & limitations of the opponents, various types of weapons at hand, the diverse & advantageous tactical zones/areas, potency, energy & effectiveness of his fighters, etc. By daybreak, waves of five battle-ready and resolute stalwarts, despite ravaged and starved bodies, stuck enemy positions. The element of surprise compounded by their lightning speed, military precision, purposive ferocity and unpredictability of the charge (from different directions), stunned the enemy. This band of few, aided by Gur Sahib’s accurate and protective archery cover, wreaked havoc across enemy lines. Plus, when the Sikh battlecry ‘Bole So Nihaal, Sat Sri Akaal’ (one who utters prospers, that timeless God is the truth), along with the salutation ‘Waheguruji Da Khalsa, Waheguruji Di Fateh’ (pure souls belong to God, and victory is always of God), reverberated in the air, stuck terror and paralyzed some enemy planks. This strategy worked and this colossal army was not able to trounce them the entire day. The valor, gallantry and resolve of the Khalsa was in full display, and not only did they die fighting till their last breath but caused heavy casualties across enemy lines. Two outstanding and magnificent martyrs that day were Gur Sahib’s own children, his eldest sons – 17 years old Ajit Singh and 14 years old Jhujjar Singh.

By nightfall, it was very evident that with only a handful of Sikhs left, that both the Fort and Khalsa defenses would fall the following day. This is when the faithful invoked the covenant of ‘Panj Pyare’ or Five Beloved. This pledge of collective authority given to ‘Five Sikhs’ was specified by Guru Gobind Singh himself in the 1699 initiation of the Khalsa ceremonies. While forming the new order, Gur Sahib declared “wherever five Sikhs of mine congregate, they shall be the highest of the high. Whatever they will do, will carry the authority of the Khalsa”, and this jurisprudence also applied to him as the sixth Khalsa initiate! Therefore, the Guru had to abide by the command and edict of the ‘Panj Pyare’ and they mandated him to leave Chamkaur, with the instructions to resurrect the Khalsa so that evil and depravity of the Turk rulers could be uprooted. It is said that before leaving, the Guru Sahib announced his departure by bellowing “Sat Sri Akal” (Eternal God alone is the truth), blew out the torches of enemy camp via his precise arrows, and clapped his hands a few times and said “Peer Hind Rahaavat” (holyman of Hind is leaving). Eventually, when the adversaries took over the Fort, to their chagrin they were unable to capture the Guru – dead or alive!

In the meanwhile, Gur Sahib slipped into the jungles of Macchiwara. While wandering there, he wrote one his very poignant shabad (hymn), ‘Mittar Pyare Nu, Haal Muridan Da Kehna’ (To my friend beloved, how do I state the condition/problem of your disciple), in which he expresses his gratitude to the Divine despite the suffering and hardships. As the Guru made his way to Dina (with enemy forces looking high and low for him), he was helped by two of his ardent Pashtun followers, Ghani Khan and Nabhi Khan. They disguised him as the ‘Uch Da Pir’ (an exalted Sufi master) from Multan and carried him on palanquin, with the front manned by the Pathan brothers and the back by his followers, Daya Singh and Dharam Singh. Thus, they cleared all check-points and orchestrated the great escape!

Meanwhile, unbeknown to the Guru, his mother (Mata Gurjari) and his two younger sons (8 year old Zorawar Singh and 6 years old Fateh Singh), who got separated from the larger group during the exodus out of Anandpur, were tricked into going to the village of ‘Saheri’ by Gangu Brahmin, their trusted household cook. Gangu deceived the family for a few gold coins and jewelry they were carrying (and for any Mughal bounty or awards this notoriety would bring). They were arrested and handed over to the Mughal Faujdar of ‘Morinda’ and eventually to Wazir Khan, the Nawab of Sirhind. In Sirhind, in the thick of winter, they were first imprisoned for seventy-two hours in an especially cold prison called the ‘Thanda Burj’ (Cold Tower) and thereafter the two minors were put on trial. Wazir Khan, having returned empty-handed from the battle of Chamkaur, wanted a full-on revenge! During the proceedings, the children were offered reprieve and gifts if they embraced Islam and converted into muslims. The children refused, and for their defiance, the tribunal ordered the children tortured and entombed alive! It is said that Sher Muhammad Khan, the Nawab of Malerkotla, openly protested this callous, unjust and cruel punishment. Whereas, Diwan Sucha Nand, another courtier, persuaded the Governor to carry out the verdict by quoting a Farsi poem by ‘Firdaus’ that, snakelets will become snakes, wolf-pups will become wolves, and these children of the Guru are like the snake neonates who will surely grow up to become a serpent just like their father, thereby, no mercy be shown to them.

So with their fate sealed, on December 26th, 1704, they were then bricked alive! It is said that when the wall was being built around them, the ‘Qazi’ (priest) again offered to pardon them if they converted, but this offer too was spurned by the minors. In the end, the wall failed and the minors were executed with the sword. When the news of their death reached their grandmother (Mata Gujari), she breathed her last upon hearing of this savage and inhumane death that was inflicted upon these innocent children. So in a span of just a few days, Gur Sahib had lost his entire family. The news of their tragic and gruesome deaths (including his mother’s demise), reached him only when he reached Raikot. Rai Kalha, the muslim ruler of Raikot, was Gur Sahib’s ardent devotee and he dispatched a messenger to Sirhind to enquire about the family’s whereabouts. When the messenger returned with this agonizing news, Gur Sahib showed great grace, serenity and stoicism despite his unsurmountable loss and unimaginable grief. Here, he also prophesied the end of the Mughal empire and Turk lineage in India.

Coming Next Part 3: The Rebuke…