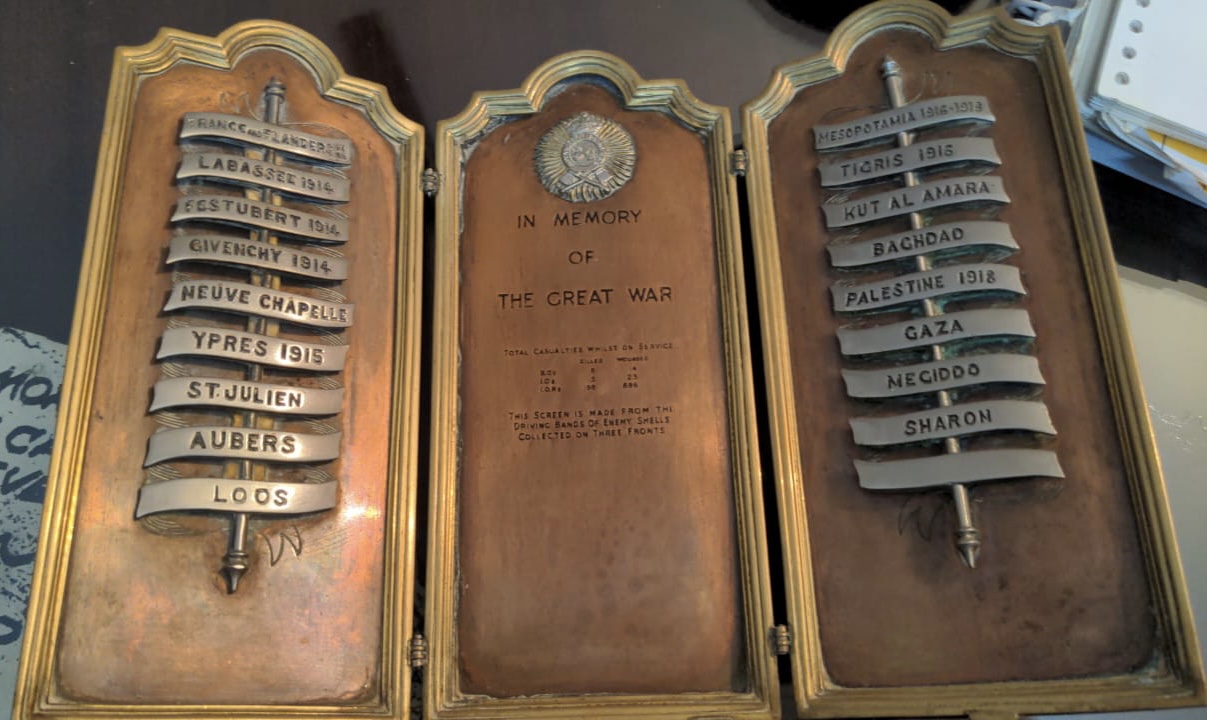

Today, on this Remembrance/Veterans Day, the world celebrates and honors the fallen soldiers of the Great War. It also commemorates the day Armistice was signed that brought World War 1 to its end. In this sea of poppies, which is considered a symbol of sacrifice, I too want to recognize and pay tribute to my ancestor Subedar Indar Singh, who saw the various theatres of war fighting the Germans in Flanders & Western Front and later the Ottoman Empire in Mesopotamia.

IEF in the Trenches

Trench Foot Inspection

Flammenwerfer

Chemical Warfare Casaulties

Part of Indian Expeditionary Force (34th Sikh Pioneers, Lahore Brigade), saw action very soon after landing in France (October 1914). As a specialized infantry regiment with expertise in engineering and construction in addition to being conventional infantry men, they quickly supported building and fortification of trenches, establishing communication lines and other infrastructure. Eager to fight, this was the first time these men from India were exposed to ‘Trench Warfare’. Needless to say, the conditions were deplorable! The trenches were mostly waterlogged; full of mud and slime that not only jammed their rifles but also caused them to develop ‘trench foot’ (and led to many a foot amputation). Add to that inclement weather for which initially they didn’t have proper protection (and they had to contend with their summer-grade Khaki uniforms, not ideal for European fall/winter weather). In addition, the trenches were filled with rats competing for their meager rations, and the soldiers had to endure instances of body-lice breakouts! There was the ‘Trench deadlock’ and to gain a few yards, each side of the warring factions faced each other across the no man’s land, and 24/7 launched repeated & aggressive trench attacks, saps and raids. This was aided by heavy artillery bombardment, constant bursts of machine guns, grenades and mortars attacks, arial bombardment and tanks ( although in their infancy), and snipers galore. Of the German armament, ‘Minenwerfers’ (mortar bombs) were the most dreaded. They were effectively used to clear obstacles, bunkers, barbed wires, parapets, sentry positions, etc., and once launched it could be heard coming and with it’s sound getting louder and louder as it approached and then exploded with great power creating a crater as big as a room! It’s psychological impact was so huge that ‘Shell-shock’ was officially recognized by the medical and psychiatric communities. As the war progressed there were even more fearsome weapons such as the ‘Flammenwerfer’ (Flamethrower) that threw/hurtled sheets of flame and smoke towards the trench soldiers and in essence burning them alive! Also, for the first time chemical warfare in the form of large-scale use of lethal poison gas where liquid chlorine was used (second battle of Ypres, 1915) followed shortly afterwards with mustard gas. Needless to say that despite such destruction and horrific conditions, neither side made any meaningful gain! Instead, both sides amassed massive and crippling casualties! Shrapnels, fragments, bullets, bodies and injured everywhere!

Having said that, the ‘Battle of Festubert’ (on November 23-24, 1914), was very pivotal for my ancestor and his regiment. According to Iain Smith (Sikh Pioneers and Sikh Light Infantry Association UK), it was the worst day for the regiment on the Western Front. They were told to take over the German trench at all cost! In the thinly manned Allied Line, the German attack decimated the 34th! 9 out of 12 British Officers were killed, wounded or went missing. Same happened to the men. Only the very experienced soldiers survived and they were instrumental in keeping the morale high and normal functioning of the regiment. One of those Indian officers was Indar Singh, and the regimental records show that he got promoted from Jemadar to Subedar on November 24th, 1914. Also the regimental effort and sacrifice was honored by the King and ‘Royal’ was added and thus the regiment was called the ‘34th Royal Sikh Regiment’. Very few regiments have been honored in this way. Also, at some point, he also received the Russian imperial order of St. Stanislaus (which was reciprocal award amongst the Allies). Plus, there has been a family story that has passed down thru the generations, that he carried his injured commanding officer (CO) 5 miles to safety. In my research, it so turned out that the men did indeed carry their CO Col. GHF Kelly 5 miles to be buried in the cemetery at Beuvry Cemetery, I am assuming my ancestor was one of those men!

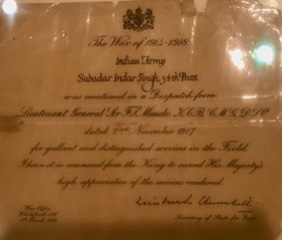

In 1917, the regiment was sent to Basra/ Mesopotamia to take part in the Ottaman empire offensive. During the ‘Battle of Daur’, General Maude mentioned him Despatch (November 2, 1917). In Kut Al Amara, he eventually got wounded with a bullet lodged in his spine. He was sent home as a war-wounded and soon afterwards, he succumbed from his war injuries during the second wave of the Spanish Flu (Oct-Nov, 1918)

Mention-in-Despatch Certificate